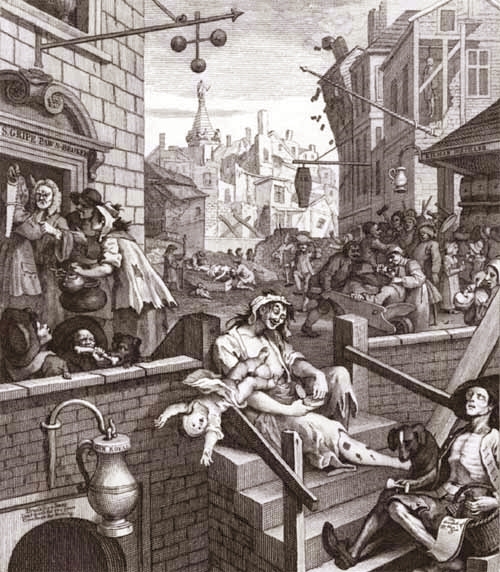

A book entitled 'A World on Fire,' by a writer named Joe Jackson, describes the roles of Antoine Lavoisier and Joseph Priestley in determining the properties and nature of air, including the discovery of oxygen.The following passage, from pp. 43,44, describes some aspects of English culture during that period: "The England of 1755 was about as peaceful and ennobling as the American West of another hundred years. Although the British saw themselves as the envy of starving, onion-eating Europe, home to lecherous Papists and mincing French courtiers, the Continent saw a much different picture. England 'is different in every respect from the rest of Europe,' noted Casanova on his travels, not the least for the violence he observed. Highways were strung with gibbeted corpses, and a man could be hung for stealing a sheep. 'Anything that looks like a fight is delicious to an Englishman,' said Henri Misson, and reasons to riot ran the gamut from the rising price of bread to the wrong play printed on a playbill. Force, rather than consensus, was the way to achieve results. 'Violence was as English as plum pudding,' states one historian, while Christopher Hibbert, in The Roots of Evil, observes that pity was a rarity. Cat-dropping, bull-baiting, bear-baiting, and cockfighting were popular sports, while 'unwanted babies were left out in the street to die or were thrown into dung heaps or open drains.' "One cause of such cruelty could be blamed on chemistry. Colin Wilson makes a good case in his History of Murder that although life was always cheap, a strange callousness to suffering rose among the British when alcohol was affordable for the rich and poor. In Elizabethan England, people drank beer, wine, sherry, mead, and cider because the water was unfit, but since such wellsprings were costly, truly rampant alcoholism was rare. That changed in 1650-60, when a Dutch chemist named Sylvius discovered that a distillation of juniper berries produced a potent spirit called geneva, French for "juniper." The drink became popular in Holland, and when William of Orange became England's king in 1689, geneva began to flow in great quantities and its name was shortened to 'gin.' "English distillers soon realized that an even cheaper and stronger spirit could be distilled from low-grade corn. When an Act of Parliament in 1690 allowed anyone to make and sell spirits without a license, gin shops filled the towns and cities and one in six houses sold gin. By 1699, the crime rate had risen so alarmingly that an act was passed making the theft of goods worth more than 5 shillings punishable by death; by 1734, eight million gallons of gin were consumed in England annually, while in London alone, the consumption rate was 14 gallons per head. Horror stories popped up everywhere. In 1734, Judith Dfour was hanged for murdering her baby: she collected it from the workhouse, where it had been freshly clothed, then stripped the infant of its garments, strangled it, threw its body in a ditch, and sold the garments for the price of gin. The Mohocks, a club of young gentlemen dedicated to "doing all possible to hurt their fellow creatures," drank themselves beyond pity before boring out the eyes of old women and prostitutes with their swords. A report in a 1748 issue of The Gentleman's Magazine described how a nurse became so drunk that, instead of laying her charge in its cradle, she placed it in the fire. When examined before a magistrate, she testified that 'she was quite stupid and senseless [with drink], so that she took the child for a log of wood; on which she was discharged.'" It seems useful to remember that such accounts as the one above should not be regarded as believable or true -- if, that is, the words "belief" and "truth" are taken to suggest that written language (or spoken language for that matter -- or the new "electronic language") can convey "absolutely reliable" pictures of the world, past or present. The quotation above is the writer Joe Jackson's summary of the writings of other writers; it is his perspective. On page 39, Mr. Jackson writes that the Royal Society each year awarded the Copley Medal "in honor of research or an invention that solved a particularly vexing [scientific] problem." And he says that "in 1753 the medal was awarded to Benjamin Franklin for his discoveries in electricity, thus making him a kind of honorary Englishman." Elsewhere it is written that Ben Franklin was an Englishman most of his life, and well into the 1770s. The longer quotation above is not believable or true in any other sense than that it is believable and true that the writer Joe Jackson wrote those words as his perspective upon that period when human beings were figuring out a certain aspect of the physical world. Words are a form of information, and as such are unrelated to truth. However, it seems plausible, given the volume of reports from the past, to assume that there was a lot of horror in the world then, even as now there appears to be.

Bob |